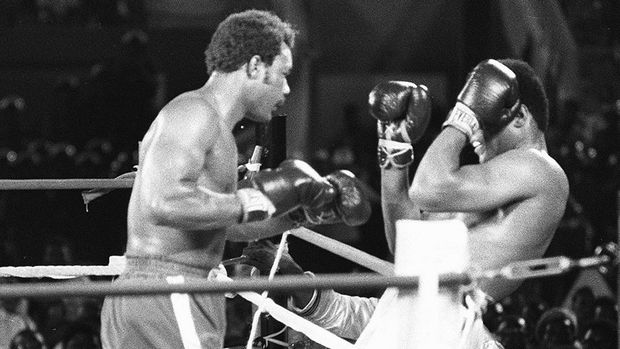

Active fund management is on the ropes.

Until fairly recently I would be nigh on certain that if I looked at the statement of any new enquirers existing pension or investment account, propping it up I’d find a stack of expensive actively managed funds from a number of the most well-marketed investment providers. But that has been changing and in the last few years, investors and advisers alike have increasingly shunned actively managed funds in favour of passive. In fact, during 2016 not only did one passive fund provider take in more new money than all of the other investment fund providers combined, but questions were being asked as to whether it was a sign of the end for active fund management.

To explain where we are and why this is happening you must first understand what active and passive fund management is.

Historically speaking, when an investor or Financial Adviser selected a fund, actively managed funds were pretty much the only game in town. Only a few passive options were genuinely considered or even accessible and the conventional wisdom was that active funds were the default option because of their ability to give investors access to a professional fund managers knowledge, experience and skill at selectively buying and selling individual shares. An ‘active’ fund manager would continually assess the holdings of the fund as well as the market environment on the behalf of their investors, trading in and out of shares with a view to producing an outsized profit either from the increasing value of prudently selected companies or from the ability to limit losses through shrewd sales. The aim of an active fund was to achieve a return that was superior to that of the market.

On the other hand, although passively managed funds have been around for quite some time, it is only within the last decade or so that there has been an explosion of choice and access. Passively managed funds remove the active seeking nature of trying to forecast the performance of selective shares, instead simply achieving the market return by buying and holding all of the shares in an index. An ‘index’ to put it simply, is a predetermined group of shares and its corresponding performance. For example, the often quoted FTSE 100 index is a group of the UK’s largest 100 companies and the index goes up and down based on the change in the value of the included companies. You can find an index for almost any market these days and investors can refer to an index to provide them with a quick representation of a given markets makeup and performance, allowing other investments to be ‘benchmarked’ against them for comparison. For example, an investor holding an actively managed UK equity fund can compare its performance against the FTSE 100 index to determine whether it is faring better or worse than the market.

But recent events and extensive research has caused investors to doubt the ability of active fund managers to do their job of outperforming their benchmark index with any regularity and with the availability of more detailed fund information and an ever expanding passive fund choice, investors have started reallocating their money away from actively managed funds and into the comparative benchmark index via low cost ‘passive’ investment funds such as ‘index tracking’ and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), which both mirror the holdings of the chosen index.

The Financial Crisis of 2008 was one such event that changed perceptions. Revered hedge funds and other actively managed fund strategies failed to protect their investors from the huge losses of that time. In fact, many investors lost as much as, if not more than the market itself, which prompted investors to question why they were paying significantly high and sometimes extortionate fees for actively managed funds if it did not improve the outcome.

Costs are indeed one of the biggest reasons why passive funds have gained so much popularity globally. With UK actively managed funds charging an average of 0.90% per annum in comparison to the passive funds average of 0.15% per annum, it is clear that after costs are deducted from fund performance, passive funds have a big advantage over their more costly alternative. To the untrained eye, the costs may appear to be small, but when they are compounded over the long term the difference can be remarkable with a £250,000 actively managed fund growing to £844,184 over 20 years at a 7% annual growth rate compared to £980,012 in a passively managed fund, creating a difference of £135,828 based on these costs differentials alone. Cost does matter and investors are increasingly coming alive to the reality that the less is paid on fund costs, the more there is remaining for the investor.

But in the UK the banning of fund commissions to advisers in 2013 is also a significant event which has further opened the door to passive funds. Prior to 2013 actively managed funds paid commission to advisers, whereas passive funds did not. By removing commission from all fund sales and making financial advice a fee-based proposition, the incentive for advisers to recommend a commission paying active fund over a nil commission passive fund has been removed. This can further explain the increased interest in passive funds.

Finally, actively managed fund performance has been under the microscope with analysis by Standard & Poors painting a poor picture, asserting that as many as 74% of the actively managed funds in the UK Equity sector fail to beat the benchmark index over a 10 year period after costs. So an investor’s chances of choosing an actively managed fund that will go on to beat the benchmark index after costs are low.

With actively managed funds facing a crisis in confidence, is the end nigh? There is no doubt that big changes are needed within the actively managed fund industry if it is to maintain its significant market share but I really don’t think active management is dead. Smart investors and advisers will correctly continue to reallocate a large proportion of assets into passive funds, but I think that if, and this is a big if, if the cost of active management reduces to combat the advance of lower cost passive funds, then that in itself may be enough to maintain some investors. And as much as this problem is well known within financial circles, in reality, unadvised, ill-advised and financially uneducated investors will simply continue to purchase expensive, well marketed, actively managed funds unaware of the limitations that they pose.

But even for some investors with investment knowledge, passive investing still goes against the psychology of their investing mandate to outperform. Regardless of the evidence, it’s just very difficult for some investors to accept that forecasting investment returns cannot be achieved with any great consistency and that achieving returns in excess of the market is as much a game of luck as it is a skill. My own take is that this debate shouldn’t necessarily be a case of exclusively pitting active against passive with no middle ground. Investors should pick their battles carefully making use of passive and if appropriate well researched, low-cost actively managed funds where they fit into the investment goal and risk profile. This approach will reduce aggregate portfolio ongoing fund costs to an acceptable level, as well as providing the opportunity to outperform that so many investors naturally want from their portfolio. Actively managed funds have much to do if they want to win back the trust of investors and advisors, but they’ve not been knocked out just yet.

Follow me on Twitter @alexandreriley