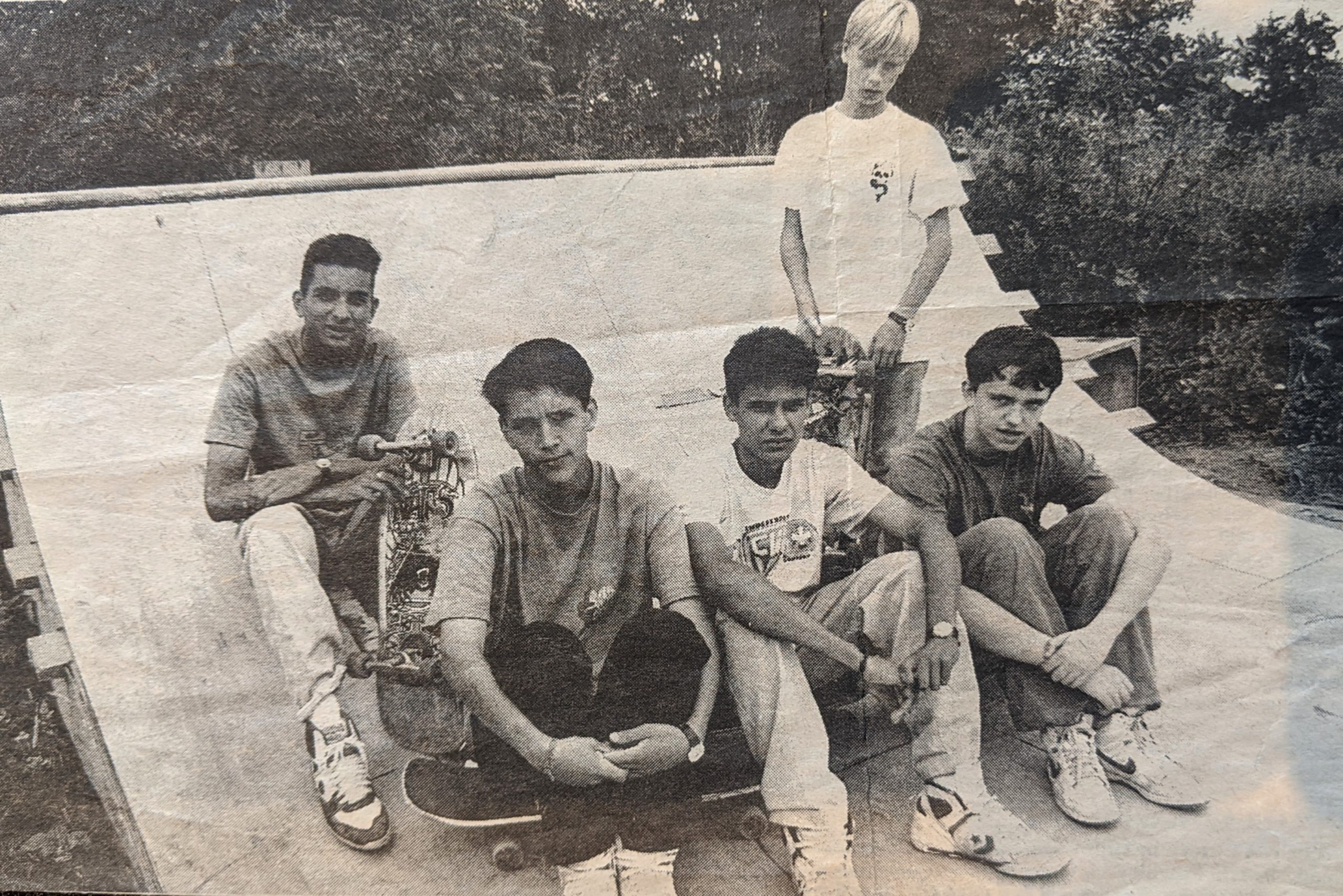

In 1989, I was a teenage skateboarder.

When school closed for summer, I’d be outside on my board every day. From sunrise to sunset my friends and I would explore London, visiting the very few skateable locations available to us at that time.

It was a brief but hugely enjoyable period of my youth, and after a few consecutive summers, we were pretty good. Not great, but good enough to fit in at most of the places we visited.

But it came with risks, and if we wanted to play, we had to pay.

And by pay, I mean sprains, cuts, bruises and for some, broken bones. They were inevitable, and an accepted piece of the whole. It didn’t matter how careful we were, at some point we did get hurt.

But we were young, so really didn’t think about the risks too much. The rewards were far greater in our young eyes.

A world away in California, also in 1989, 21-year-old professional skater Tony Hawk was pushing his own boundaries. And that of skateboarding in general.

You might have heard of Tony Hawk. To this day he makes a great career out of skateboarding. Originally crossing over to mainstream recognition through his monumentally successful video game ‘Pro Skater’. Released in 1999, the video game series went on to sell well over a billion copies. But even today at the age of 52, Tony still skates enthusiastically, is now a respected investor and businessman, whilst continuing to be the face of skateboarding to most of those outside the lifestyle.

And as we all like to reminisce over carefree times in our lives, through the power of social media I’ve kept up to date with Tony’s world through his Instagram account (6.4M followers), which recently made me think about a different perspective of risk.

Last month Tony posted an update referring to a complicated trick he started trying in 1989. What caught my attention was not the trick itself (unbelievable as it is to those who know) but because of his reference to the risk he takes to complete it.

In his Instagram post Tony says of the trick:

“They’ve gotten scarier in recent years, as the landing commitment can be risky if your feet aren’t in the right places. And my willingness to slam unexpectedly into the flat bottom has waned greatly over the last decade. So today I decided to do it one more time… and never again.”

Understandably, the risk of serious injury and the repercussions are too high for Tony on this one now. Tony has nothing to prove, and I’m sure he has far better things to do than visit the hospital and rehab if it goes wrong.

There is more to lose at this point than there is to gain.

And as Tony puts it, his ‘waning willingness to slam’ is something successful investors should pay heed to.

I’ve written about the role risk plays in achieving investment goals before. But what if you’re fortunate enough to have reached the point where you have already saved enough to meet your lifetime needs?

Continuing to shoot for the stars at this point comes with the risk of an unnecessarily outsized investment decline, potential permanent loss, and a failed financial plan.

In his book ‘The Psychology of Money’, Morgan Housel writes a chapter called ‘Getting Wealthy vs Staying Wealthy’. In it he writes:

“Getting money requires taking risks, being optimistic and putting yourself out there. But keeping money requires the opposite of risk taking. It requires humility, and fear that what you’ve made can be taken away from you just as fast. It requires frugality and an acceptance that at least some of what you’ve made is attributable to luck, so past success can’t be relied upon to repeat indefinitely”.

If you are comfortably on track to, or already can, independently finance your lifestyle goals, why continue to take outsized risks? Sure, you need to take some risk to achieve real returns, but there comes a point when there is nothing more to gain.

So, be like Tony. If you don’t need to do it anymore, park your outsized risk-taking to history. You’ll always have the memories, and your assets to show for it.

Follow me on Twitter @AlexandreRiley

My youth. From a local press cutting. London 20th July 1989